If she needs money again, let her call the bank, not me, — Maria snapped, deleting her mother-in-law’s number from her phone

“You’re making that sour face again. Maybe it’s time to see a gastroenterologist?” Elena smirked, not bothering to glance over her shoulder. She was slicing onions for a salad. Her hand trembled slightly, and the knife hit the cutting board with a dull, tired thud.

“Did you even hear what I said?” Dmitri moved closer, placing both palms on the kitchen table. They were as limp as his resolve.

“What now?” Elena sighed, wiping her hands on a dish towel before finally turning to face him. “Don’t tell me it’s another ‘small amount’ for your mother again.”

“Well, yes. Just a bit. Fifteen thousand.” He hesitated. “She… she really needs it.”

“Oh, I bet. Is it for her manicure this time? Or another emergency retreat to Sochi to recover from her ‘emotional trauma’?” Elena crossed her arms, her tone weary rather than harsh. The kind of fatigue that clings to you like old grease on a kitchen wall.

“She has a loan. She can’t pay it. She’s really struggling.” Dmitri’s voice sparked, desperate — like a candle flickering in a storm.

“She took it out herself, didn’t she? Let her pay it off. I’m not her ATM, Dmitri. And you’re not her life coach. If you’re happy being the guy caught between two women, congrats — you just got promoted to full-time punching bag.”

“She’s my mother. I can’t just abandon her,” he said, voice rising.

“And me? What am I then? Just your live-in bank account with a good credit score?” Elena stepped closer, eyes sharp. “I’ve been working two jobs since January. Saving up for a car — my car. My dream. Not so your mom can go mall-hopping with a brand-new purse.”

Dmitri dropped into a chair at the table, pressing his hands to his face like they could hide his guilt.

“You’re cruel, Lena. She’s sixty years old.”

“Uh-huh. And she behaves like a spoiled sixteen-year-old whose daddy buys her everything. And FYI, ‘she’s sixty’ is not an excuse to order sushi every other night and then cry about how ‘the interest just keeps piling up.’”

“She’s had a hard life…”

“Dmitri, you’re a grown man with a passport. You’re married. Living in an apartment you haven’t contributed a ruble toward. And you sit here telling me your mother is some poor damsel in distress. So what does that make me? The evil queen with a calculator?”

He stood up sharply, his face darkening.

“Here we go again. You’re always nagging. Everything’s about ‘have to,’ everything is on a schedule. Even sex — like clockwork, Tuesdays at 9 p.m.”

“Uh-huh. And only if your mother doesn’t call with another ‘urgent situation.’ Like last week, when she texted you a vacuum cleaner link during dinner.”

“Because hers broke down!” he yelled, more to defend himself than the vacuum cleaner.

Elena laughed — not from amusement, but from sheer helplessness.

“Tell me the truth. Did you marry me, or her?”

He went quiet.

And that silence… it had become the soundtrack of their marriage.

Elena turned back to the stove. The kettle had long since boiled. Steam curled toward the ceiling like their arguments — suffocating, repetitive, impossible to ignore.

“I’m not giving her a kopek, Dima. Not fifteen thousand, not five. Zero. Every ruble I save is for the car. I’m done riding the bus after night shifts, listening to people argue or blast music next to me.”

“That’s selfishness,” he mumbled.

“No. That’s adulthood. Selfishness is a grown woman buying cosmetics with borrowed money and expecting her son’s wife to clean up the mess.”

He stood in the middle of the kitchen like a man who had lost something precious. But what he’d lost wasn’t tangible. It was dignity. Connection. Love.

“And if I give her the money anyway?” His voice trembled. Not with anger — with fear. The kind that asked silently, Will you leave me then?

“Then pack your bags and go to her. You don’t even need to text. Just go.”

He didn’t reply. His lips moved slightly, as if to speak, but the words didn’t come. Or maybe he realized they would only make things worse.

That night, he slept on the couch.

She — in the bedroom.

Between them wasn’t a wall. It was a chasm. Of resentment, expectations, and unlived dreams.

For the first time in six years of marriage, Elena didn’t set her alarm. Let tomorrow come without a plan.

Dmitri lay silently in the dark, staring at the ceiling. His phone lit up on the coffee table. A message from “Mom”:

“How’s Lena? Still not dead from being bitter?”

He didn’t respond. But his fingers trembled.

For the first time, he realized what real debt looked like — and who he owed it to.

Saturday began with him attempting to make porridge.

He ended up with what Elena would’ve called “wallpaper glue in a bowl.” She didn’t come out of the bedroom. Just lay there, eyes tracing the cracks on the ceiling, as if waiting for an answer from above on how to live with a man who feared his mother more than his own wife.

Dmitri paced near the bedroom door like a student waiting outside the principal’s office.

“Elena…” he called gently, pushing the door open a little. “I made breakfast. Want some?”

“If you stirred your excuses into it — no,” she replied flatly, still not turning toward him.

He sat on the edge of the bed, defeated. The morning light bled into the room like diluted sorrow.

“Please. Try to understand. My mom’s… really in trouble.”

Elena turned her face to him at last — not in anger, but with a sadness so deep it echoed.

“And we aren’t?”

“She has ‘it bad’ every time I have a dream,” Maria turned and sat on the bed, elbows on her knees. “Did you notice? As soon as I start planning something — Elena Petrovna has a tooth problem, or the bank, or depression, all timed perfectly so I start thinking: she’s getting my texts from the bank.”

“You’re exaggerating,” Alexey frowned.

“Exaggerating? Let’s recall. Two years ago I was saving for courses — she got sick. Six months ago I wanted to start a business — her fridge burned out. And now I want to buy a car, and what? Again, poor, unfortunate victim of capitalism. With a debt her son somehow has to pay. That means me.”

“It’s not that simple,” he mumbled. “She really has no one except us.”

“She has no one because she burned everyone in the emotional crematorium,” Maria went to the window. “Her friends ran away because listening to her about her golden son is impossible without sedatives. Relatives disappeared because, forgive me, she stole other people’s raspberry bushes from the dacha ‘for cuttings.’ And you still believe she’s poor and unfortunate.”

“You don’t understand!” Alexey snapped. “She raised me alone! Alone, you know? Without help! Without a man! She worked hard!”

“And now she thinks she’s entitled for life,” Maria stepped closer, her voice hardening. “And who am I? An extra account in her bank?”

“You’re wrong,” he exhaled.

“No, Lyosh. You’re wrong. You’re not a husband. You’re a courier. Delivering money and excuses. I don’t want to live like this. I shouldn’t live like the second woman in the house. The woman of your life should be one. But you have two. Only one’s in the bedroom, the other on the phone.”

“Are you giving an ultimatum?”

“I’m putting a period, Lyosh. I’m not against helping. But when your mother pretends her problems are more important than ours, and you participate in it, I’m not a wife. I’m a statistic.”

Alexey sat, looking down. He wasn’t angry. He was… weak. That’s how he grew up. His mother decided everything for him. Then Maria. He just drifted. And now — he was sinking.

“I… I’ll talk to her,” he finally said.

“It’s too late,” Maria spread her hands. “I already said — I won’t give a single kopek. And you know, if after all this you send her money — I’ll understand everything.”

He nodded heavily as if a bag of sins had been hung around his neck. Got up and went to the hallway. Put on shoes.

“I’ll go to her. Talk. Maybe… somehow explain.”

Maria didn’t answer. Just watched him button his jacket. Slowly, awkwardly. Like a man who first realized: you can’t sit on two chairs any longer.

Alexey arrived at his mother’s around noon. Khrushchyovka building. Second floor. The smell of cats and boiled onions was already in the stairwell.

“Oh, you showed up,” Elena Petrovna greeted him in a colorful robe, curlers in her hair, lipstick. Red. Like her confidence in being right.

“Mom, we need to talk,” he started immediately, without taking off his coat.

“What, Masha yelled at you again… oh, sorry, ‘Maria’? Must be. So cultured. By the way, I wasn’t rude to her. She’s the one humiliating you.”

“Mom. Enough. I can’t keep begging my wife for money because you’re always in debt.”

“And who’s your wife? Your savior? I don’t care. She’d even take your socks if she could!”

“Mom. I’m serious.”

“I’m not! I gave you my life! And now you crawl before this… this… whining snake?!”

He looked at her like a stranger. She yelled, screamed, threatened — as usual. But now he heard only an echo in her voice. Empty, irritated, powerless.

“I won’t give you any money.” He said it quietly but firmly. “And I won’t ask Masha either.”

Mother fell silent. For a moment.

Then slapped him on the cheek. Not hard. But not playfully.

“Pathetic. Henpecked,” she hissed.

Alexey silently turned and left.

And for the first time in his life, didn’t look back.

He came home when it was already dark. Maria sat at the table with a cup of tea.

He took off his jacket and approached.

“I didn’t give her money,” he said simply.

“And she kicked you out?” Maria asked without emotion.

“Yes.”

“Well then,” she stood up. “Welcome to adult life.”

He looked at her as if for the first time.

As if all this time she stood at the other end of the room, in the shadows. And now — stepped into the light.

“I want to change everything,” he said.

“Then start with yourself, Lyosh. Not with your mother’s debts.”

And she went to the bedroom.

He stayed in the kitchen. Alone with the silence.

This time, it wasn’t angry. Just honest.

Sunday. Maria woke up early. The house smelled of coffee and fresh bread — Lyosha was trying. Trying quietly, carefully, as if afraid to disturb the fragile truce they’d signed yesterday without words.

He put a cup in front of her.

“With sugar. The way you like it.”

She looked at him. He seemed like a stranger. Not the one she shared everyday life, shopping, and endless talks about the dollar exchange rate with. This man stood before her with the eyes of someone who first stepped out of his mother’s shadow.

“I’ll go to Igor today,” he said. “I want to find out if he can help with mom’s loan. At least with advice. I won’t give her money. But we need to understand how she can get out of this.”

“Why?” Maria put down the cup. “She’s an adult. She made this mess — let her clean it up. That’s adult life.”

“Well, I can’t just abandon her…”

“I can.” She stood up. “Because I’m not thirteen, and I don’t have to earn anyone’s approval, especially a woman’s. Neither your mom’s, nor the downstairs neighbor’s, nor even yours.”

He was silent.

Maria stepped closer:

“I’m so tired of being third in your life. You belong to your mom. You always did. Even on our honeymoon you called her three times a day.”

“I understand…” he whispered.

“No, Lyosh. You don’t. You’re afraid. More than you love. And I won’t be with a man who’s afraid anymore.”

He sat down. Put his hands on his knees. His shoulders dropped.

“I don’t want to lose you.”

“And I don’t want to lose myself.” Maria took her jacket from the hanger. “I’m moving out.”

“Where?”

“To my own place.”

He didn’t ask any more questions. And it was the first time. No offense, no reproach. Just nodded. He understood.

A week later Maria rented a one-room apartment near the metro. No renovations, but with courtyard-facing windows and freedom. The first days she drank tea from a disposable cup and slept on a mattress. But she felt better than she had in the last two years.

Lyosha wrote. Calmly. Without hysterics.

“I’m working with a psychologist. I want to figure things out. I don’t know what will happen. But I want to be better.”

She didn’t reply immediately. She thought.

Elena Petrovna also wrote. A whole essay about how Masha destroyed her son, took away his masculinity, and anyway — this generation is selfish. At the end was a postscript:

“Live however you want. But don’t think I’ll forget.”

News in the same category

Their daughter disappeared in 1990, on the day of her graduation. And 22 years later, the father found an old photo album

We'll live off our daughter-in-law; she has a good job," the mother-in-law shared with her friend

While the woman was doing a deep cleaning of the house, she came across an old letter from her deceased husband. Carefully unfolding it, she skimmed through the lines… and froze

This Girl Spent 6 Years Fixing Her Jaw & After the Final Surgery, She Stunned Everyone with the Results – Her Transformation in Pics

'Mom, Do You Want to Meet Your Clone?' – What My 5-Year-Old Said Uncovered a Secret I Wasn't Ready For

You’re nobody without me,» my husband declared. But a year later, in my office, he begged me for a job

An eight-year-old child saved his sister during a severe snowstorm. But where were their parents at that time?

We’ll live off our daughter-in-law; she has a good job,» the mother-in-law shared with her friend

Lenočka, pay the utility bills. You have the money,” the mother-in-law asked again

Tired and confused, she spent the night at the station, having run away from her son and with no idea where to go

There’s a man hurting a girl!» — the child screamed, terrified, grabbing her mother’s hand. Lena glanced toward the bushes… and felt a chill run through her. Her heart froze

Your bonus is very timely, your sister needs to pay rent for the apartment six months in advance,” the mother ordered

Andrey sat opposite Olga, tapping his fingers on the tabletop.

A 70-year-old elder let a stranger stay overnight — at night, the village woke up to her screams. When they found out what happened, they shuddered

I found a little girl by the railroad tracks, raised her, but after 25 years her relatives appeared

A woman left a baby at the doorstep of an orphanage in the freezing cold. But after some time…

After 25 years, the father came to his daughter’s wedding — but he was turned away… And moments later, the crying spread among everyone present

Honey, I gave your sister the trip voucher, she needs it more — she’s going through a crisis, — her husband blinked innocently, having stolen his wife’s vacation

News Post

Afraid of Surgery, the Woman Used This for 6 Years to Shrink Her Tumor Based on a Tip – Oncologist’s Four Words Left Everyone Stunned

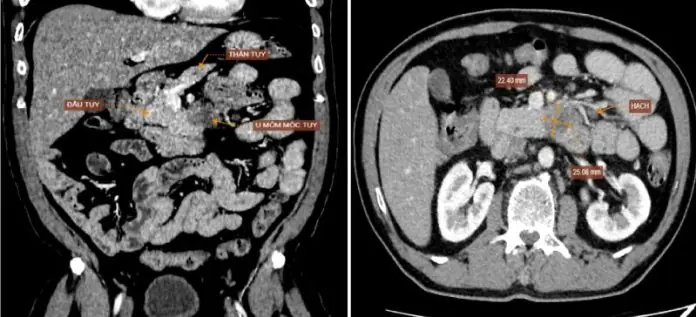

Discovered to Have One of the Deadliest Cancers After Just One Warning Sign

The Surprising Benefits of Drinking Turmeric Water at Night: 8 Reasons You Should Make It a Habit Today 🌙

Cloves, Ginger, and Lipton Tea: A Health-Boosting Trio Worth Gold

New Tiny Machine Removes Cholesterol from Arteries Without Surgery

Powerful Simulation Reveals How Cancer Progresses and Ultimately Causes Death

At My Husband’s Birthday Party, My Son Pointed and Said, 'That’s Her. The Same Skirt.'

My Husband Took Me on a Surprise Cruise — But When I Opened the Door, Everything Fell Apart

My Wife Found a Midnight Hobby – It Nearly Drove Our Neighbors Away

I Got Seated Next to My Husband’s Ex on a Flight – By the Time We Landed, My Marriage Was Over

One Day, I Saw a 'Just Had a Baby' Sticker on My Boyfriend's Car — But We Never Had a Baby

Never Throw Away Lemon Peels Again: 12 Unusual Ways to Use Them

How People Over 50 Can Supplement Fiber for Better Health

Unleash Your Inner Alpha: The Natural Nighttime Boost You Need

Stop Now! These 8 Pumpkin Seed Mistakes Trigger Irreversible Reactions in Your Body

The photograph of a little boy who became one of the most recognizable men today

Three Family Members Diagnosed with Thyroid Nodules – The Mother Collapses: “I Thought Eating More of Those Two Things Prevented Cancer”

A Family of Four Siblings Diagnosed with Stomach Cancer – Doctor Shakes His Head: Two "Deadly" Common Habits Many People Share

A 49-Year-Old Man Dies of Brain Hemorrhage – Doctor Warns: No Matter How Hot It Gets, Don't Do These Things