Study Reveals Reading is a Complex, Flexible Brain Process Involving Multiple Interacting Neural Networks

Every time your eyes scan a page whether it’s a dog-eared paperback or a glowing phone screen your brain performs one of its most complex feats without you even noticing. In a fraction of a second, it turns abstract symbols into sound, meaning, memory, and sometimes even emotion. It’s a silent act of alchemy that happens so quickly, so fluently, that it feels almost effortless.

But effortless doesn’t mean simple.

Behind the quiet act of reading lies a neurological symphony one so sophisticated that even the most advanced artificial intelligence can’t fully replicate it. More than 3,000 brain scans across 163 studies now reveal what’s really going on beneath the surface: reading is not a singular task, but a dynamic collaboration of multiple brain networks adapting in real time. Visual areas recognize shapes, language centers decode meaning, motor systems simulate speech, and memory pathways thread it all together.

Why does a nonsense word like sproke make you pause to sound it out, while a familiar word like love floats in with instant clarity? Why does reading silently require your brain to “speak” internally, without making a sound? And why does the cerebellum region once thought to be limited to balance and movement activate when you’re deep in a novel?

These questions aren’t just curiosities for scientists. They reveal something essential about the human mind: its astonishing flexibility. Reading doesn’t just reflect intelligence it builds it. And the more we understand how it works, the more we begin to see reading not as a passive skill, but as a quiet, daily act of cognitive transformation.

The Hidden Complexity Behind Every Word

A meta-analysis conducted by the Max Planck Institute, encompassing over 3,000 participants and 163 brain imaging studies, revealed that reading is not managed by a single “reading center” in the brain. Instead, it activates a distributed network of regions, each contributing its own specialized function. This network includes areas responsible for visual recognition, language processing, memory retrieval, attention control, and even motor planning.

Here’s how the process unfolds: as your eyes take in text, the visual cortex begins decoding letter shapes and spatial patterns. When those letters form a recognizable word, temporal regions interpret meaning, drawing on past experience and vocabulary. Move into a full sentence, and frontal and parietal lobes jump in structuring grammar, anticipating what comes next, and aligning everything with your goals and context. Meanwhile, working memory keeps previous words and ideas active so that you can maintain coherence across the sentence or paragraph.

Even the cerebellum, traditionally associated with physical coordination, plays a surprising role. During silent reading, it helps sequence your internal speech and manage the rhythm of comprehension essentially coordinating mental “movement” in much the same way it choreographs your physical balance.

The true marvel lies in how seamlessly this system operates. The brain doesn’t just perform more when reading becomes challenging it performs differently, strategically selecting new routes, adapting networks, and recalibrating in real time. Encountering a dense philosophical passage versus a lighthearted novel? Your brain shifts its approach accordingly, drawing on different configurations of its vast neural toolkit.

How the Brain Reads in Real Time

When your eyes land on a letter, the visual cortex immediately recognizes its shape and orientation. But as soon as that letter becomes part of a word, your brain doesn’t simply intensify the same activity it switches strategies. Frontal and parietal regions come online to assess structure, retrieve meaning, and place that word into context. The temporal lobe draws from stored knowledge to associate the word with concepts, emotions, and experiences. And when you process an entire sentence or paragraph, working memory and predictive processing mechanisms guide your attention, connect ideas, and anticipate what’s next.

This coordination isn’t linear it’s layered. Your brain isn’t just reading a word and then moving on; it’s simultaneously interpreting grammar, inferring tone, and projecting possible meanings based on what’s already been read. And this real-time reconfiguration is precisely what sets human readers apart from machines. We don’t read mechanically we read interpretively.

Mode matters, too. Reading aloud activates your auditory cortex and motor-speech regions, linking visual input to the physical actions of speaking. But silent reading, often considered a quieter or more passive act, actually demands more of your brain’s internal control systems. You suppress the urge to vocalize while simulating an inner voice, using executive networks to maintain focus and coherence without external cues. The cerebellum, once thought to be uninvolved in higher cognition, shows consistent activation in this mode fine-tuning your internal rhythm and mental pacing as you “hear” the words silently.

Even more remarkable is the brain’s sensitivity to word familiarity. A well-known word like “house” triggers a rapid memory-based response, pulling meaning from established neural connections. But when you encounter an unfamiliar or invented word like “plisk,” the brain switches to phonological processing, sounding it out using internalized spelling-to-sound rules. This isn’t a fallback it’s an intentional, adaptive rerouting that underscores your brain’s capacity for problem-solving on the fly.

Ultimately, every sentence you read is like a live script and your brain is not just performing it, but adapting the script, directing the cast, and designing the set in real time. This deeply coordinated process doesn’t just enable reading it mirrors the very way we think, plan, and engage with the world. In reading, we see the mind in motion: attentive, agile, and endlessly creative.

The Dual Pathways of Reading: Speed vs. Strategy

Every time you read a word, your brain makes an invisible decision one that happens so quickly you never notice it, yet it determines how you process language. Neuroscience reveals that this decision hinges on two core pathways: one optimized for speed, the other for strategy.

The lexical-semantic route is the brain’s fast lane. It’s the path you take when you recognize a familiar word like light or music. This route taps into your mental dictionary, retrieving a word’s sound, meaning, and emotional associations almost instantly. It’s fluent, automatic, and relies on memory systems in areas such as the angular gyrus and inferior temporal sulcus regions that specialize in turning visual symbols into rich, conceptual knowledge.

But not all words come preloaded. When you stumble upon something unfamiliar like sproke or glanter your brain reroutes to the phonological pathway. This system decodes words step-by-step, using sound-letter rules you learned as a child. It’s slower, more effortful, but crucial for tackling new vocabulary, foreign languages, or oddly spelled words like colonel. This route engages phonological and auditory regions, constructing meaning through active problem-solving.

What’s most fascinating is that your brain doesn’t just use one or the other it switches between them dynamically, depending on familiarity, context, and even emotional tone. Encounter a rare word in an otherwise simple sentence? Your brain might start with the phonological route but loop in semantic systems to speed things up. See a common word used in a strange or ironic way? The brain rechecks its assumptions and recalibrates interpretation on the fly.

These two pathways are not competitors they’re collaborators. One provides efficiency; the other ensures adaptability. This interplay aligns with connectionist models of reading, which propose that sound, meaning, and structure are not processed in isolation but in constant interaction. In practice, this allows the brain to fluidly balance recognition and reasoning, turning static text into dynamic understanding.

Crucially, this dual-system approach also helps explain why reading can be challenging for some individuals. For example, people with dyslexia may have impairments in phonological processing, making new or irregular words harder to decode. On the other hand, limited vocabulary or language exposure can weaken the lexical route, slowing down reading fluency. Understanding these systems isn’t just an academic exercise it has direct implications for how we teach, support, and empower readers across all ages and abilities.

Why Reading Strengthens the Brain

Reading does far more than deliver information it rewires the brain. Each sentence you decode, each idea you grasp, is not just understood but integrated, stretching and strengthening the very networks that allow you to think, focus, and adapt. At its core, reading is an exercise in cognitive flexibility the brain’s ability to shift gears, change strategies, and respond to new challenges with agility.

This flexibility is not theoretical. Neuroimaging studies show that the brain’s reading networks especially the lateral frontoparietal network, midcingulo-insular system, and frontostriatal loops reconfigure themselves depending on the demands of the text. When you silently read a complex passage, your brain toggles between regions that suppress vocalization, simulate internal speech, and maintain attention. If you’re reading poetry, it might activate areas attuned to rhythm and metaphor. A technical manual? Expect more effort from memory and reasoning centers. Each genre, each format, trains a slightly different cognitive “muscle.”

And like muscles, these networks grow stronger with use. Regular readers tend to show higher activity in regions tied to comprehension, attention control, and semantic integration. In fact, individuals who perform better on reading comprehension tasks tend to display greater variability and responsiveness in their brain network, a marker of neurological agility. It’s not just about reading more; it’s about how well the brain adapts while doing so.

This capacity for growth extends across the lifespan. A pivotal study from the Max Planck Institute found that even adults learning to read for the first time some well into middle age experienced structural brain changes. These changes weren’t limited to language centers; they reached deep into the thalamus and brainstem, areas once thought to be fixed. Learning to read reshaped how the brain organized and timed its internal signals, proving that plasticity isn’t just for the young it’s a lifelong potential.

Conversely, when these networks are impaired, the effects ripple outward. Conditions such as ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, mood disorders, and dementia often show disruptions in the same systems that support flexible reading. These disruptions can affect more than literacy they can compromise attention, memory, and even emotional regulation.

A Mental Resistance to Distraction

Neuroscience reinforces what many readers intuitively know: reading isn’t just passive absorption, it’s active mental labor. And that labor is increasingly at odds with the fragmented way we consume information online. Skimming articles, hopping between tabs, and scanning for key points may feel productive, but they activate only limited circuits in the brain. Over time, this habitual skimming can weaken our ability to focus, comprehend, and reflect especially when deep concentration has been replaced by what researchers call “cognitive impatience.”

In contrast, deep reading engages the very neural systems responsible for executive control, memory consolidation, emotional empathy, and abstract reasoning. It activates areas that help us construct mental models, infer subtext, and tolerate ambiguity. These are not just reading skills they are life skills. The ability to hold complexity, to delay judgment, to question assumptions these are the same abilities we rely on in relationships, decision-making, and civic engagement.

What’s more, sustained reading strengthens what psychologists refer to as “top-down attention” the capacity to direct and maintain focus deliberately. In an age where most inputs are designed to hijack your focus from the outside (bottom-up), the ability to choose where your attention goes is both rare and vital. This is particularly important for young people, whose attentional systems are still developing, and for adults seeking to maintain mental sharpness amid information overload.

Reading also serves as an antidote to the flattening effects of digital algorithms, which tend to reinforce what we already believe. A novel can introduce you to minds unlike your own. A complex essay can challenge your assumptions. Reading doesn’t just inform you it stretches you. It invites you into unfamiliar perspectives and teaches your brain to accommodate difference.

As our daily habits become more screen-saturated, this kind of deliberate, immersive reading becomes not just important but urgent. It’s not about resisting technology; it’s about resisting passivity. Choosing to read deeply even for a few uninterrupted minutes a day, is a powerful way to preserve the neural systems that help us think deeply, connect meaningfully, and respond wisely.

A Daily Act of Cognitive Renewal

Every time you pick up a book, scroll through a thoughtful article, or reread a challenging paragraph, you’re doing far more than consuming information you’re training your brain to think, feel, and adapt. Neuroscience confirms what lifelong readers often feel but couldn’t quite explain: reading doesn’t just change what you know. It changes how you think.

Through reading, the brain engages in a kind of daily recalibration strengthening attention, honing comprehension, and practicing the cognitive flexibility needed to navigate an ever-changing world. The act of toggling between meaning and memory, decoding unfamiliar words, or following a narrative thread over time is not a passive pastime it’s a high-level mental workout that improves emotional intelligence, decision-making, and perspective-taking.

In a culture that increasingly prioritizes reaction over reflection, reading offers a powerful counterbalance. It invites us to pause, question, and imagine. To read deeply is to resist the pull of instant gratification in favor of intentional growth the kind that unfolds line by line, idea by idea.

And perhaps most importantly, reading reminds us of our own neuroplastic potential. The brain is not fixed. It can be stretched, strengthened, rewired. Whether you’re a child learning to decode, an adult reading to stay sharp, or an older adult seeking to preserve cognitive agility, reading remains one of the most accessible, transformative tools we have.

So next time you find yourself immersed in a story, grappling with a dense essay, or simply savoring a well-turned phrase, ask yourself not just What am I learning? but What is this teaching my brain to become? Because reading is never just about the words on the page. It’s about the mind you’re building behind the scenes one page, one pathway, one transformation at a time.

News in the same category

Scientists Turn Coffee Waste Into Bricks—And They’re Twice as Strong as Standard

The Amount of Electricity Now Being Generated From Solar Is Unbelievable

Scientists Turn Coffee Waste Into Bricks—And They’re Twice as Strong as Standard

Australia Is Using 3D Printers To Save Coral Reefs, And The Fish Are Already Moving In

Planet Earth Has Been Spinning Faster Lately

Goodbye Nursing Homes! The New Trend Is CoHousing With Friends

Global warming could permanently shift rainfall patterns, affecting water access for 2 billion people worldwide, study shows.

The Amount of Electricity Now Being Generated From Solar Is Unbelievable

Scientists Discover Cosmic Glitch That Challenges Everything We Know About Gravity—And May Mean Our Universe Is an Illusion

The Reason Dogs Chase People? Causes And Care Tips From A Vet

‘Hand Of God’ Appears In Ultrasound After Mom’s Prayer For Baby’s Health

Scientists Warn Rogue Star Could Knock Earth Out Of Orbit, Triggering Global Freeze

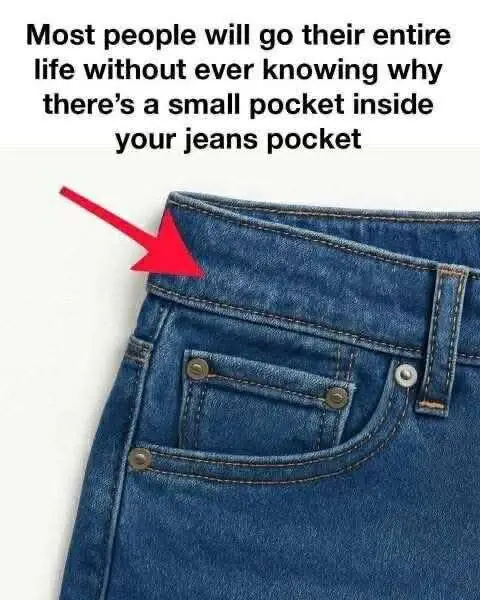

The story behind the tiny pocket on your jeans

Tsunami Warning Issued After Monster 7.3 Earthquake — Americans Evacuate Coastal Areas

Tips for Keeping Dogs Safe During Fireworks Celebrations

Buzz Aldrin ‘Admits’ Moon Landing Was Fake? Here’s What He Actually Said

Archaeologists Unearth 2,000-Year-Old ‘Jesus Boat’ Near Sea Of Galilee

Restaurant Forced to Compensate 4,000 Customers After Teenagers Filmed Themselves ‘Peeing in Hotpot Broth’

News Post

Proven Health Benefits of Celery & Nutritional Facts (Evidence-Based)

Mold Illness: What It Is, Hidden Signs, and How to Protect Your Home

80% of Heart Attacks Are Preventable: Embrace These 5 Simple Habits

Is Cancer Hereditary? Helpful Tips to Prevent the Growth of Cancer Cells

Warning from Hospitals: Eating This Type of Meat Every Day Can Increase Cancer Risk – Don’t Be Complacent!

3 Pain Areas on the Body That Could Signal Early-Stage Cancer: Don’t Delay, or It Could Spread

What Your Ankle Bracelet Really Says About You — It’s More Than Just Jewelry

Truth behind viral statement after married CEO caught with employee on Coldplay kiss cam

DIY Okra Face Gel Recipe for Radiant, Firm Skin: Collagen Boosting Skincare Solution for Glowing Skin

By incorporating this okragel into your nightly skincare routine, you can enjoy smoother, firmer, and more radiant skin in just a few simple steps.

Homemade Rice Face Cream: A Simple, Natural Skincare Solution to Achieve Radiant Glass Skin in 7 Days

It’s time to create the DIY rice face cream that will help you achieve glowing, glass-like skin in just 7 days.

Natural Solutions for Gout: Tackling Uric Acid to Prevent Pain

Don't Ignore These 15 Common Cancer Symptoms: A Guide to Early Detection

5 Hidden Nutritional Deficiencies You Likely Have (and How to Fix Them)

Scientists Turn Coffee Waste Into Bricks—And They’re Twice as Strong as Standard

The Amount of Electricity Now Being Generated From Solar Is Unbelievable

3-Year-Old Girl Bites and Swallows Mercury from a Broken Thermometer — Her Mother’s Quick Thinking Saves Her Life and Earns Praise from Doctors

More and More Young People Are Suffering from Colon Cancer — Doctors Warn: Eat Less of These 3 Things!

Diagnosed with Late-Stage Stomach Cancer, I Painfully Realized: 3 Foods Left Too Long in the Fridge Were the "Accomplices"