Early-Life Stress Alters Astrocytes, Increasing Depression Risk—but the Damage May Be Reversible

When people think about the brain, they often picture neurons firing electrical signals to control thoughts, emotions, and behavior. Yet neurons do not work alone. They are supported by a vital network of helper cells known as glial cells, among which astrocytes play a particularly important role. Astrocytes do not transmit electrical impulses themselves, but they regulate chemical balance, supply nutrients, protect neurons, and help maintain healthy communication within brain circuits. Emerging research now suggests that these support cells may be deeply affected by stress early in life—and that these changes could significantly increase the risk of depression later on.

Recent studies indicate that early-life stress can disrupt astrocytes in a brain region called the lateral hypothalamus, an area involved in regulating mood, motivation, sleep, and energy balance. According to neuroscientists, chronic exposure to stress hormones during childhood—such as cortisol—can interfere with specific receptors located on astrocytes. Under normal conditions, these receptors help astrocytes respond appropriately to the brain’s needs. However, when stress hormones overwhelm the system, astrocytes begin to malfunction.

At the cellular level, stressed astrocytes undergo noticeable structural changes. They shrink in size, lose their branching extensions, and become less complex overall. This is critical because astrocytes rely on their branching structure to interact with multiple neurons at once. Research published in journals such as Nature Neuroscience and Molecular Psychiatry shows that when astrocytes lose these connections, communication between neurons becomes less efficient and less stable. As a result, entire neural circuits involved in emotion and motivation may fall out of balance.

These biological disruptions appear to translate directly into behavior. In animal models, altered astrocyte function has been linked to depressive-like symptoms, including reduced motivation, decreased interest in normally rewarding activities, increased lethargy, and disturbances in sleep–wake cycles. Experts from institutions such as the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) note that these behaviors closely resemble key features of human depression, strengthening the case that astrocytes play an active role in mental health rather than serving as passive support cells.

One of the most compelling aspects of this research is the discovery that the damage caused by early-life stress may not be permanent. Scientists found that when they blocked stress hormone receptors specifically in astrocytes, many of the harmful effects were reversed. Even after structural damage had already begun, shutting down these receptors allowed astrocytes to regain some of their lost complexity. At the same time, depressive-like behaviors were significantly reduced. This suggests that astrocytes retain a degree of plasticity and can recover under the right conditions.

These findings open the door to new approaches for treating depression. Traditionally, most antidepressant therapies focus on neurons and neurotransmitters such as serotonin or dopamine. However, researchers from leading institutions like Harvard Medical School and the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research are increasingly emphasizing the importance of glial cells in psychiatric disorders. Targeting astrocyte networks—particularly in individuals who experienced early adversity—may provide more effective and longer-lasting treatments.

In conclusion, this growing body of research challenges the long-held neuron-centered view of depression. It suggests that early-life stress can alter the brain’s support system at a fundamental level, increasing vulnerability to mood disorders later in life. At the same time, the possibility of reversing astrocyte damage offers hope. By developing therapies that restore healthy astrocyte function, future treatments may better address the root causes of depression, especially for those shaped by early-life stress.

News in the same category

Rapid Pain and Stiffness Relief in Knee Osteoarthritis

Burglar Uncovers Shocking Crime During Robbery, Turns Himself In and Exposes Serious Offense

The Black Diamond Apple: A Rare Gem from the Mountains of Tibet

Marvin Harvin Becomes One of the First Incarcerated Individuals to Graduate from Yale University, Highlighting the Power of Education in Prison Reform

Warren Buffett’s Ice Cream Quote: A Simple Yet Powerful Lesson on Taxes

Why Do Button-Down Shirts Have Loops On the Back

World's Oldest Little Blue Penguin Reaches Remarkable 25 Years in Managed Care

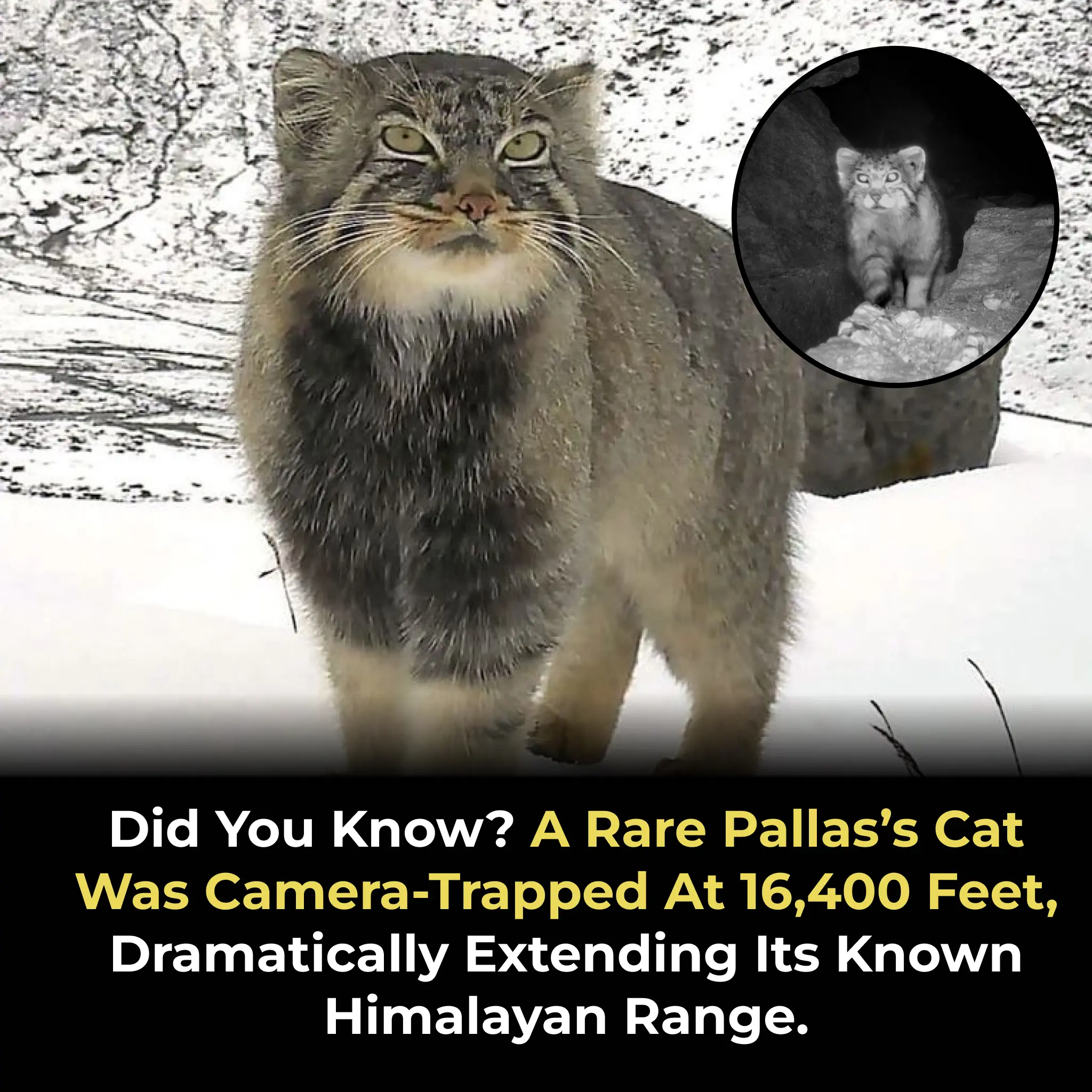

Rare Sighting of Pallas's Cat at 16,400 Feet in the Himalayas Reveals Remarkable Adaptability

Studies Suggest Links Between Swearing, Staying Up Late, and Higher Intelligence

Kenya Records Historic Elephant Baby Boom in National Park: 140 Calves Born in One Year

Photograper Captures A Once-In-A-Lifetime Shot Of A ‘Horizontal Rainbow’ That Filled The Whole Sky

Afghan Men Detained for Dressing Like "Peaky Blinders" Characters, Authorities Claim Promotion of Foreign Culture

Austrian Man Arrested for Manslaughter After Leaving Girlfriend to Freeze on Grossglockner Peak

Midea Group Unveils MIRO U: A Revolutionary Six-Armed Super Humanoid Robot for Factory Automation

A Touch of Viking Brilliance: Moss-Carpeted Homes in Norway

China Conducts World’s First Wireless Train Convoy Trial, Moving Nearly 40,000 Tons of Cargo

Gene-Edited Immune Cells Reverse Aggressive Blood Cancers in World-First Human Trial

Dutch Artist Berndnaut Smilde Creates Fleeting Indoor Clouds to Explore Transience and Atmosphere

Starlings Obscure the Sky Over Rome: A Dystopian Viral Photo

News Post

A Massive Spider Megacolony Thriving in a Sulfur-Fueled Cave Ecosystem

Rapid Pain and Stiffness Relief in Knee Osteoarthritis

Tamarind: The Tangy Superfruit Your Body Will Thank You For

Why Your Legs Show Signs of Aging First — and 3 Drinks That Can Help Keep Them Strong

Intensive Gum Disease Treatment Slows Artery Thickening, Benefiting Heart and Brain Health

The #1 Food Proven to Support Kidney Cleansing and Protection

High Olive Oil Intake Linked to Significantly Lower Risk of HER2-Negative Breast Cancer

Tight Junction Proteins and Permeability Improved by Roasted Garlic in Mice with Induced Colitis

Randomized Controlled Trial Confirms NEM® Efficacy and Safety in Reducing Osteoarthritis Pain and Stiffness

Whole Fish Trumps Pills: Study Finds Whole-Food Factors, Not Isolated Omega-3s, Lower Autism Risk

Dark chocolate and tea found to significantly lower blood pressure

Burglar Uncovers Shocking Crime During Robbery, Turns Himself In and Exposes Serious Offense

The Black Diamond Apple: A Rare Gem from the Mountains of Tibet

The Power of Pine Needles: 30 Benefits and Homemade Uses

Marvin Harvin Becomes One of the First Incarcerated Individuals to Graduate from Yale University, Highlighting the Power of Education in Prison Reform

The Hidden Power of Pistachio Shells: Benefits and Clever Homemade Uses

Warren Buffett’s Ice Cream Quote: A Simple Yet Powerful Lesson on Taxes

Papaya Seeds: A Powerful Remedy for Liver Health and How to Use Them as a Pepper Substitute

30 Amazing Benefits of Lactuca serriola (Wild Lettuce)