Thirteen Year Old Boy Becomes First Person Cured of Once Untreatable Brain Cancer

For decades, one diagnosis has struck fear into doctors, parents, and researchers alike: diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, better known as DIPG. This rare and aggressive brainstem cancer has long been considered universally fatal. There were no known survivors, no curative treatments, and no meaningful way to stop its rapid progression. Families who heard the diagnosis were often told to focus on comfort, not recovery.

Then came Lucas.

Diagnosed at just six years old, Lucas was given the same prognosis as every other child before him—mere months to live. Yet against all medical precedent, after receiving an experimental treatment in a clinical trial, Lucas became the first documented human in history to be fully cured of DIPG. His case has since reshaped how scientists think about this devastating disease and reopened questions once thought settled forever.

This is not only a story of scientific breakthrough, but also one of resilience, precision medicine, and the fragile moment when “impossible” quietly becomes “possible.”

A Diagnosis Once Considered a Death Sentence

Lucas’s illness began with symptoms that were troubling but not immediately alarming. He had trouble walking straight, suffered unexplained nosebleeds, fainted unexpectedly, and experienced difficulties with bladder control. As the symptoms escalated, doctors ordered imaging scans that revealed the unthinkable: a tumor deep within his brainstem.

The diagnosis was DIPG.

DIPG develops in the pons, a vital area of the brain that controls breathing, heart rate, sleep, and motor function. Because the tumor grows diffusely—intertwined with healthy brain tissue—it cannot be surgically removed. Chemotherapy has consistently failed to stop it, and radiation only slows progression temporarily without offering long-term survival (National Cancer Institute).

Each year, approximately 300 children in the United States and up to 100 in France are diagnosed with DIPG. Median survival is around nine months, and fewer than 10 percent live beyond two years (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute). Until Lucas, there had never been a confirmed cure.

Dr. Jacques Grill, a senior pediatric oncologist at Gustave Roussy Cancer Centre in Paris, recalled having to tell Lucas’s parents that their son would not survive. The conversation was not about treatment success, but about preparing for loss.

The BIOMEDE Trial: A Last Door Left Open

Unwilling to accept the finality of the diagnosis, Lucas’s parents, Cedric and Olesja, searched relentlessly for alternatives. Their efforts led them from Belgium to France, where Lucas became one of the first children enrolled in the BIOMEDE clinical trial—a groundbreaking study focused on molecularly targeted therapies for DIPG (European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer).

BIOMEDE represented a shift away from one-size-fits-all cancer treatment. Each child underwent a biopsy so researchers could analyze the tumor’s molecular profile and assign drugs based on its unique biology. This approach alone was revolutionary in DIPG care, where biopsies were historically avoided due to risk.

Lucas was randomly assigned a drug called everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor already used in cancers of the kidney, breast, pancreas, and certain brain tumors. However, it had never successfully treated DIPG.

Everolimus works by blocking the mTOR pathway, which cancer cells rely on to grow, divide, and build blood supply. Theoretically, it could starve tumors of their ability to expand—but no one knew if it could penetrate the brainstem or meaningfully affect DIPG cells.

Doctors hoped it might buy time. No one expected a cure.

When the Tumor Didn’t Just Shrink—It Vanished

From the earliest MRI scans, Lucas’s response stunned his medical team.

Instead of stabilizing or shrinking slightly, the tumor steadily disappeared. Month after month, scan after scan, there was less cancer visible—until eventually, there was none.

According to Dr. Grill, this had never been observed in DIPG patients, even among so-called “long responders.” Other children in the BIOMEDE trial experienced delayed progression, but only Lucas showed complete eradication of the tumor (Nature Medicine).

Doctors hesitated to stop treatment. There was no precedent to guide them. Then came an even more astonishing revelation: Lucas had quietly stopped taking everolimus on his own over a year earlier.

The cancer still did not return.

At that moment, medicine crossed a historic threshold. Lucas was officially declared cured—the first known survivor of DIPG.

Why Did It Work for Lucas?

The joy of Lucas’s recovery was accompanied by urgent scientific questions. Why did everolimus succeed so completely in his case and not in others?

Researchers believe the answer lies in an extremely rare genetic mutation found in Lucas’s tumor. Molecular analysis showed that this mutation made his cancer cells unusually dependent on the mTOR pathway, rendering them uniquely vulnerable to everolimus (The Lancet Oncology).

In short, Lucas’s tumor had a biological “Achilles’ heel.”

This discovery reinforces a central truth in oncology: cancers with the same name can behave very differently at the molecular level. DIPG is not one disease, but many—each driven by distinct genetic mechanisms.

Organoids, Precision Medicine, and the Road Ahead

Following Lucas’s case, researchers began developing tumor organoids—lab-grown 3D models designed to replicate DIPG behavior. By recreating Lucas’s tumor biology in the lab, scientists hope to understand how to reproduce similar drug sensitivity in other tumors (Nature Reviews Cancer).

The long-term goal is transformative: instead of waiting for rare mutations to appear naturally, doctors could one day engineer vulnerabilities into tumors, making them responsive to existing drugs.

However, experts caution that translating these insights into widely available treatments may take 10 to 15 years (Institut Gustave Roussy). Still, for the first time, DIPG research is driven by evidence of success rather than despair.

Why This One Case Changes Everything

Lucas’s cure does not mean DIPG is solved—but it fundamentally changes the question scientists are asking. The focus has shifted from “Can DIPG ever be cured?” to “How can we make this happen again?”

His story underscores several critical lessons:

-

Precision medicine saves lives.

-

Rare genetic mutations can unlock new treatments.

-

Clinical trials are essential, even when outcomes seem uncertain.

-

Diseases once deemed untreatable may still hold hidden weaknesses.

Today, Lucas is 13 years old, five years cancer-free, attending school, making plans, and living a life once thought impossible.

A New Beginning, Not an Ending

Lucas’s survival marks a turning point in pediatric oncology. He is living proof that even the most lethal cancers may not be beyond reach. While one cure does not equal a universal solution, it lights a path forward.

Hope, once abstract, is now grounded in data.

For families facing a DIPG diagnosis today, that shift means everything.

Sources

(National Cancer Institute)

(Dana-Farber Cancer Institute)

(European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer – BIOMEDE Trial)

(Nature Medicine)

(The Lancet Oncology)

(Inserm France / Gustave Roussy Cancer Centre)

News in the same category

Overview Energy's Bold Plan to Beam Power from Space to Earth Using Infrared Lasers

Japan’s Ghost Homes Crisis: 9 Million Vacant Houses Amid a Shrinking Population

Japan’s Traditional Tree-Saving Method: The Beautiful and Thoughtful Practice of Nemawashi

Swedish Billionaire Buys Logging Company to Save Amazon Rainforest

The Farmer Who Cut Off His Own Finger After a Snake Bite: A Tale of Panic and Misinformation

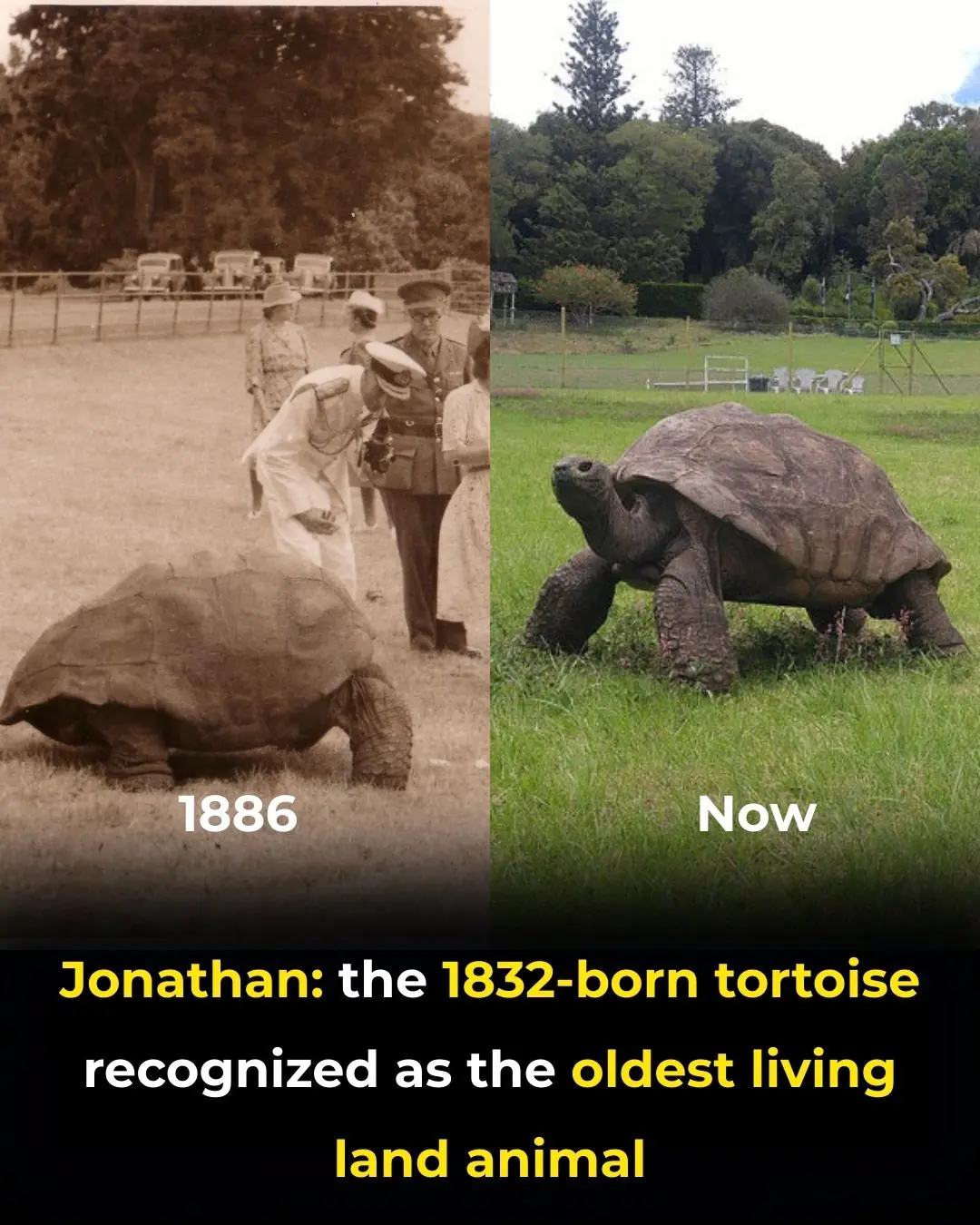

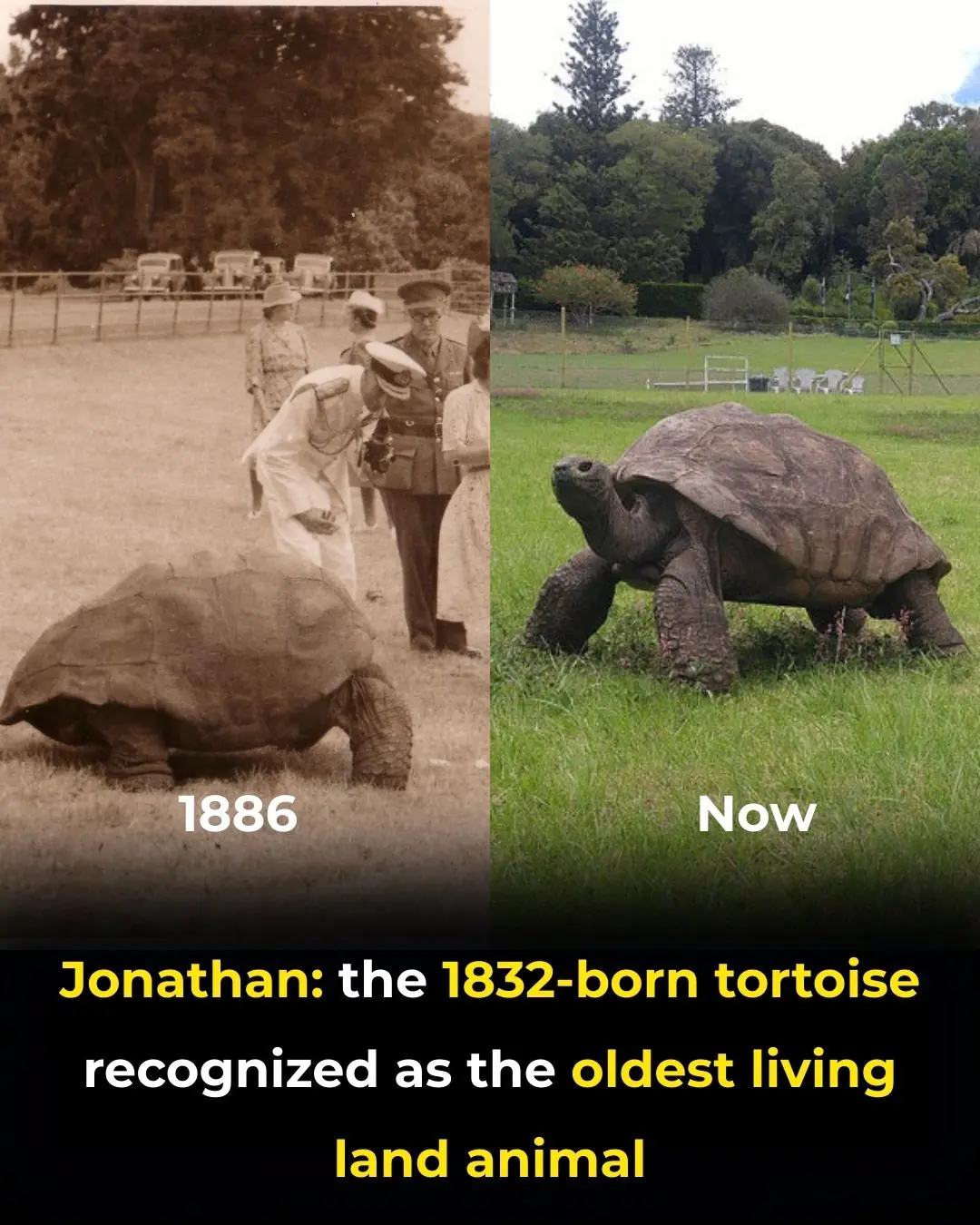

Meet Jonathan: The 193-Year-Old Tortoise Who Has Witnessed Three Centuries

Hawaii’s Million Mosquitoes a Week: A Bold Move to Save Endangered Birds

Scientists Achieve Historic Breakthrough by Removing HIV DNA from Human Cells, Paving the Way for a Potential Cure

Belgium’s “Pay What You Can” Markets: Redefining Access to Fresh Food with Community and Solidarity

China's Betavolt Unveils Coin-Sized Nuclear Battery with a Potential 100-Year Lifespan

Japan’s Morning Coffee Kiosks: A Quiet Ritual for a Peaceful Start to the Day

13-Year-Old Boy From Nevada Buys His Single Mother a Car Through Hard Work and Dedication

ReTuna: The World’s First Shopping Mall Built on Repair, Reuse, and the Circular Economy

Revolutionary Cancer Treatment Technique: Restoring Cancer Cells to Healthy States

The Critical Role of Sleep in Brain Health: How Sleep Deprivation Impairs Mental Clarity and Cognitive Function

Scientists Discover The Maximum Age a Human Can Live To

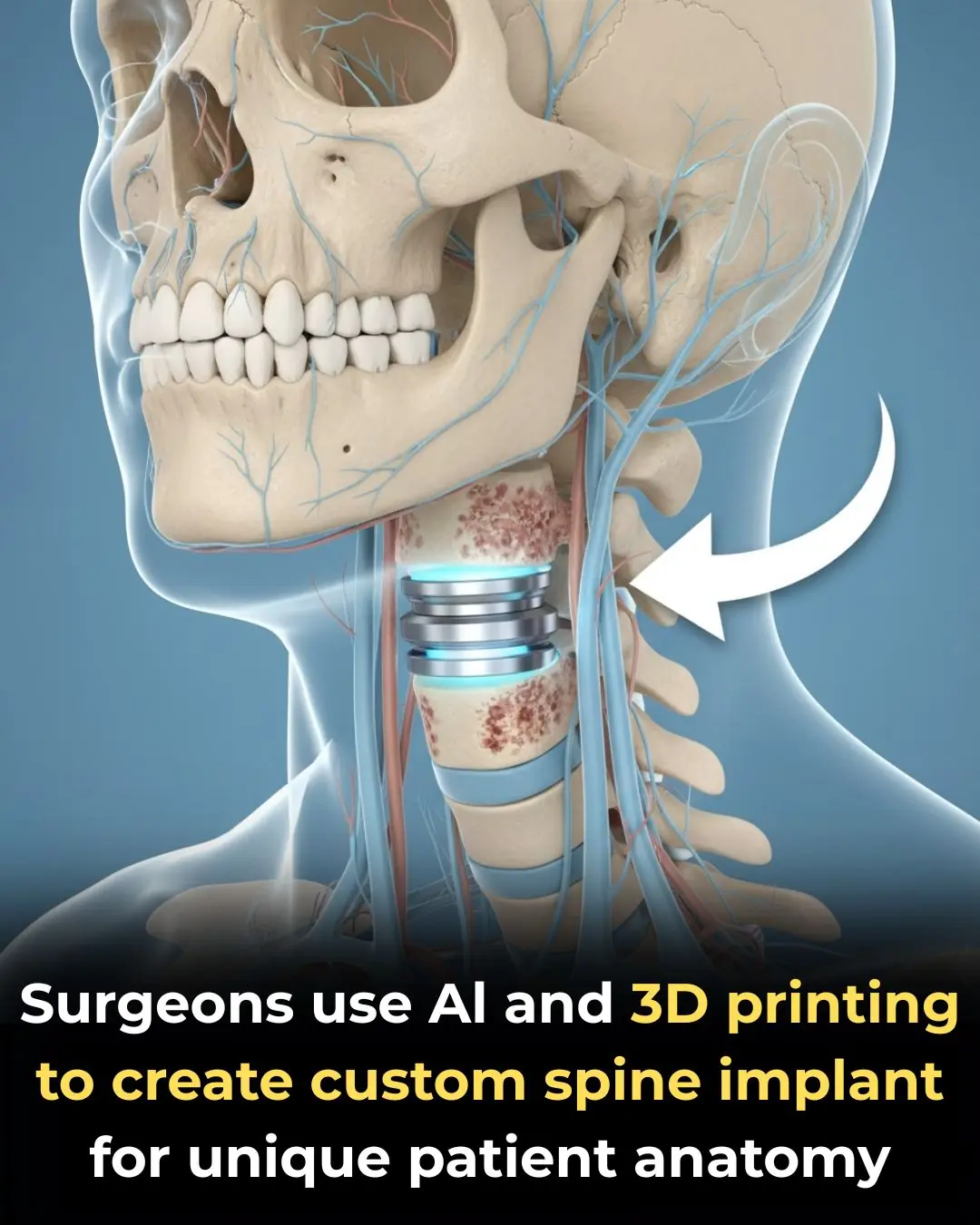

UC San Diego Health Performs World’s First Personalized Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery Using AI and 3D Printing

Could Your Blood Type Be Influencing How You Age

Promising Early Results for ELI-002 2P: A New Vaccine Targeting Pancreatic Cancer

News Post

Tiny Pumpkin Toadlet Discovered in Brazil's Atlantic Forest: A New Species of Vibrantly Colored Frog

Overview Energy's Bold Plan to Beam Power from Space to Earth Using Infrared Lasers

Japan’s Ghost Homes Crisis: 9 Million Vacant Houses Amid a Shrinking Population

Japan’s Traditional Tree-Saving Method: The Beautiful and Thoughtful Practice of Nemawashi

Swedish Billionaire Buys Logging Company to Save Amazon Rainforest

The Farmer Who Cut Off His Own Finger After a Snake Bite: A Tale of Panic and Misinformation

Meet Jonathan: The 193-Year-Old Tortoise Who Has Witnessed Three Centuries

Hawaii’s Million Mosquitoes a Week: A Bold Move to Save Endangered Birds

Scientists Achieve Historic Breakthrough by Removing HIV DNA from Human Cells, Paving the Way for a Potential Cure

Belgium’s “Pay What You Can” Markets: Redefining Access to Fresh Food with Community and Solidarity

China's Betavolt Unveils Coin-Sized Nuclear Battery with a Potential 100-Year Lifespan

Japan’s Morning Coffee Kiosks: A Quiet Ritual for a Peaceful Start to the Day

13-Year-Old Boy From Nevada Buys His Single Mother a Car Through Hard Work and Dedication

ReTuna: The World’s First Shopping Mall Built on Repair, Reuse, and the Circular Economy

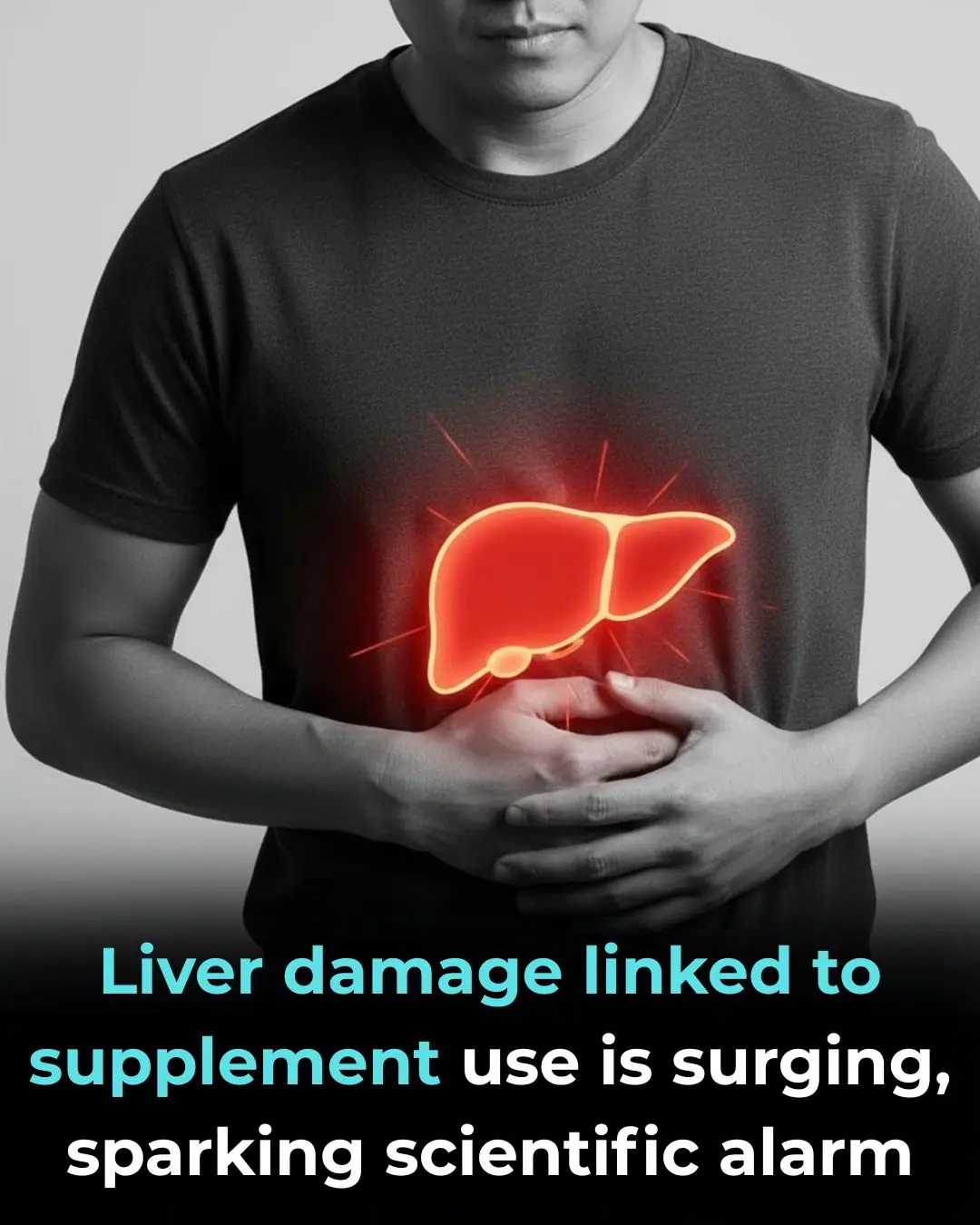

Liver Damage Linked to Supplement Use Is Surging, Sparking Scientific Alarm

No More Fillings? Scientists Successfully Grow Human Teeth in the Lab

Lab Study Shows Dandelion Root Kills Over 90% of Colon Cancer Cells In Just Two Days

7 Red Flag Phrases Narcissists Use to Exert Control During Arguments

Although they're both peanuts, red-shelled and white-shelled peanuts have significant differences. Read this so you don't buy them indiscriminately again!