Female Frogs Fake Their Death to Avoid Mating With Males They Don’t Like

Playing Dead: How Female European Common Frogs Outsmart Males in a Breeding Frenzy

When danger strikes in the animal kingdom, creatures usually have three choices: fight, flee… or, in some extraordinary cases, play dead. Opossums collapse into limp stillness when predators get too close. Certain dragonflies drop suddenly from the sky, feigning lifelessness to avoid an unwanted mate. And now, scientists have discovered a surprising new member of this “dramatic survival” club: the female European common frog.

Each spring, as ice retreats from still ponds, these unassuming amphibians gather by the hundreds, racing to reproduce during a frantic, two-week sprint. For males, it’s a ruthless numbers game — the more mates, the better. For females, it’s a dangerous gauntlet. Dozens of eager males can swarm a single female, forming what biologists call a “mating ball,” a suffocating knot of limbs that often leads to exhaustion, injury, or even death. In this chaos, subtle refusals simply don’t work. Survival demands creativity.

Now, researchers have revealed that some females have evolved a remarkable counter-strategy. When escape seems impossible, these frogs go limp, stiffen their limbs, and drift like lifeless bodies. The tactic, which scientists call tonic immobility, often tricks the males into letting go. Moments later, the “revived” female swims away unharmed, unmated — and alive.

This theatrical performance does more than secure a narrow escape. It overturns long-held assumptions that female frogs are passive participants in the breeding frenzy. Instead, it highlights the subtle but powerful ways these small, quiet creatures reclaim agency in a high-stakes contest for survival.

The High-Pressure World of Explosive Breeding

For the European common frog (Rana temporaria), breeding season isn’t a leisurely courtship; it’s a brutal, tightly compressed event biologists call explosive breeding. This intense reproductive window lasts anywhere from a few days to two weeks, depending on water temperature and weather conditions.

As soon as the first ponds thaw, males converge in huge numbers, their chorus of croaks filling the air. They far outnumber females, creating an atmosphere of intense competition. In their urgency, males will latch onto nearly any moving body — sometimes even other males, or members of different frog species entirely.

The result is chaos: mating balls where multiple males cling desperately to a single female, pushing and shoving in the water. The term sounds almost whimsical, but the reality is grim. The combined weight and thrashing can pin a female underwater, preventing her from surfacing for air. For many, this dangerous encounter ends in drowning.

For decades, scientists assumed females had little recourse — that their only option was to endure the ordeal until the males eventually disengaged. But recent research paints a different, far more dynamic picture: females aren’t just passive victims. They’re active problem-solvers, evolving a surprising repertoire of defenses that can mean the difference between life and death.

The Study That Changed Everything

The breakthrough came from a seemingly straightforward experiment. Ecologist Carolin Dittrich and herpetologist Mark-Oliver Rödel from the Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science in Germany originally set out to explore a simple question: do males prefer females of a particular size? Since larger females tend to lay more eggs, evolutionary theory suggests males should target them preferentially.

To test this, the researchers placed two females — one large, one small — in a tank with a single male and observed the trio for an hour. But what they discovered was far more intriguing than mate size preferences.

Across dozens of interactions, females exhibited consistent, deliberate behaviors aimed at escaping the males’ grip — behaviors that had never been formally documented before in this species. Out of 54 instances of clasping, females repeatedly employed strategies that ranged from physical to auditory to outright theatrical.

The data were striking:

-

83% of clasped females attempted body rotation, twisting their bodies to loosen the male’s grip.

-

48% produced release calls, low-frequency sounds similar to the “wrong target” signals males emit when accidentally clasped by other males.

-

33% displayed tonic immobility, going stiff and still until the male let go.

Interestingly, smaller females were both more likely to use these tactics and more successful at escaping, possibly because their lighter frames make slipping away easier. These findings, published in Royal Society Open Science, challenge the idea of female passivity during explosive breeding and highlight the quiet sophistication of frog survival strategies.

Three Clever Tactics for Survival

The females’ strategies fall into three clear categories — each with its own purpose and risks.

1. Body Rotation – The Twist to Freedom

The most common defense involves twisting or rolling their bodies, forcing the male to adjust his grip. In some cases, this maneuver flips the male into a dangerous position, leaving him momentarily vulnerable to drowning. The disruption often buys the female just enough time to break free and escape the scrum.

2. Release Calls – Sounding the “Wrong Target” Alarm

Nearly half of the females emit a grunt-like call that mimics the rejection signal males give when mistakenly grabbed by rivals. This clever deception works because males rely on quick reflexes, not careful evaluation, in the chaotic environment of the pond. Hearing the familiar sound, they release their hold almost instantly.

3. Tonic Immobility – Playing Dead

The rarest but most dramatic tactic is total stillness. A female stiffens her body, extends her limbs, and drifts like a lifeless form. Sometimes, she maintains this act for minutes, even while being dragged underwater. Confused or repelled, the male eventually lets go, and the “dead” frog springs back to life, swimming off to safety.

Why Evolution Favors These Behaviors

These tactics are a direct response to sexual conflict — the evolutionary mismatch between male and female priorities. Males maximize success by mating with as many females as possible during the narrow breeding window. Females, by contrast, can reproduce only once per season, making survival — not multiple pairings — their top priority.

Avoidance strategies like rolling, calling, or feigning death likely evolved because they reduce immediate physical danger without requiring costly fights or complex mate selection. In explosive, high-density breeding environments, subtlety isn’t enough — quick, adaptive tactics are the only way to survive.

A Strategy Seen Across Nature

Although tonic immobility in a mating context is rare among vertebrates, similar strategies exist throughout the animal kingdom.

-

Dragonflies, such as the moorland hawker, drop motionless to the ground to avoid further mating after laying eggs.

-

Spiders sometimes resort to cannibalism, ending unwanted encounters permanently.

-

Mallard ducks have evolved intricate corkscrew-shaped reproductive tracts to thwart forced copulations, leading to an evolutionary arms race with equally complex male anatomy.

-

In primates, some females form coalitions to fend off aggressive males, while others mate with multiple partners to confuse paternity and reduce the risk of infanticide.

For European common frogs, however, these tactics are unique in that they are not about choosing better mates but purely about staying alive long enough to reproduce.

Conservation and Ecological Lessons

Beyond behavioral insights, this discovery carries important conservation implications. European common frogs, like many amphibians, face increasing threats from habitat loss, climate change, pollution, and emerging diseases.

Explosive breeders are especially vulnerable because their entire reproductive success hinges on access to safe ponds during that brief window each spring. If habitat fragmentation forces larger numbers of frogs into fewer ponds, the intensity of mating balls — and the danger to females — could rise sharply.

By studying when and how females use these avoidance behaviors, ecologists can design better conservation strategies. Creating multiple small ponds rather than one crowded site, maintaining connectivity between habitats, and reducing human disturbance during the breeding season could all improve survival odds for females.

The Quiet Power of Adaptability

In the loud, chaotic energy of a breeding pond, a female frog’s stillness might seem insignificant. But in that quiet act of defiance — limbs locked, body drifting, pulse steady — lies an extraordinary story of resilience. These frogs are not decorated singers or flamboyant dancers; they survive because they are adaptable, strategic, and unafraid to use every tool evolution has given them.

Their story is a reminder that in nature, power doesn’t always roar. Sometimes it floats silently, waiting for the perfect moment to slip free and swim away.

News in the same category

Researchers Find Higher Intelligence Is Correlated With Left-Wing Beliefs and Seems to Be Genetic

Urgent Health Warning Issued After Pigs With ‘Neon Blue’ Flesh Are Discovered in One Specific Part of the Us

'Hostile' comet aimed at Earth could obliterate the world's economy 'overnight' if it hits

Iconic movie sequel delayed until 2027 after online sleuths 'guessed the plot'

Don’t Sleep With Your Pets

The Secret Meaning of the Letter “M” on Your Palm

The Remarkable Journey of Tru Beare, Who Was Born Weighing Only One Pound

Researchers Create Injectable Hydrogel to Boost Bone Strength

If You Have Moles on This Part of Your Body

The Purpose of the Small Pocket in Women’s Underwear

Can You Spot the Hidden Number?

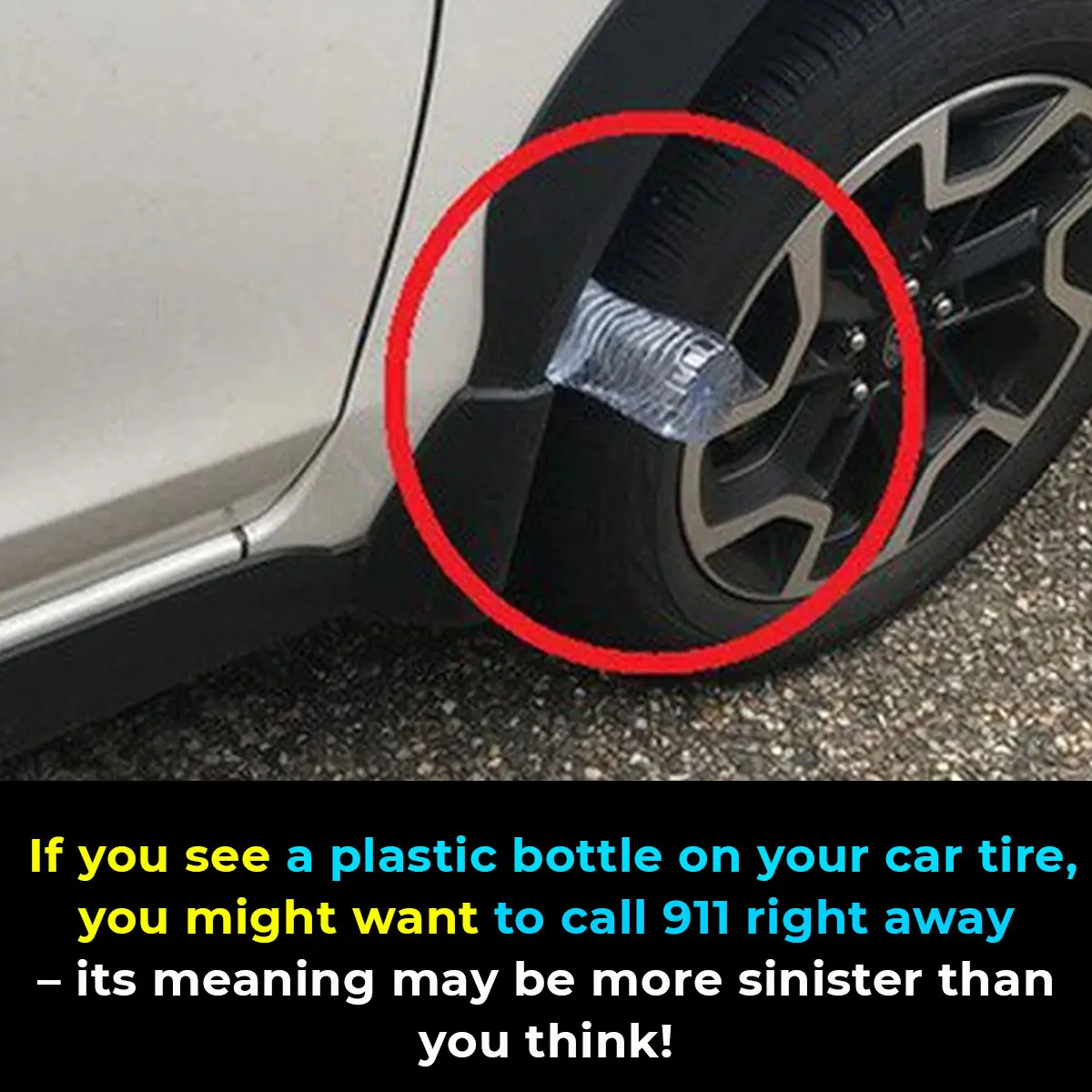

Beware of the Plastic Bottle Scam: A New Car Theft Tactic

Chinese Scientists Say They Created a Cure for Type 1 Diabetes

Rob Gronkowski forgot he invested $69,000 in Apple and ten years later the value has completely changed his net-worth

Scientists discover that powerful side effect of Ozempic could actually reverse aging

Scientists warn ancient Easter Island statues could vanish in a matter of years

NASA astronaut describes exactly what space smells like and it's not what you'd expect

Subtle Signs Your Passed Loved One Is Watching Over You

What Does a Thumb Ring Really Mean

News Post

The Hidden Truth About Tinnitus: Why That Ringing in Your Ears Shouldn’t Be Ignored

Over time, repeated noise trauma damages tiny hair cells inside the cochlea, which cannot regenerate, resulting in permanent hearing changes and tinnitus.

DIY Turmeric & Ginger Shots to Fight Inflammation, Boost Immunity & Soothe Your Gut

Coconut water: Is It Good for You, Nutrition, Benefits, Side Effects (Science Based)

Clean Arteries: 10 Foods to Eat Daily

10 Warning Signs of Parasites in Your Body

Diet and Uric Acid: Foods to Avoid for Gout Prevention

Hiker Encounters Massive Snake Camouflaged Along South Carolina Creek

8 Foods That Help Eliminate Cancer Cells

David Quammen, the COVID Predictor Warns of New Pandemic Threats

Natural Remedies to Address Skin Tags, Warts, and Blackheads

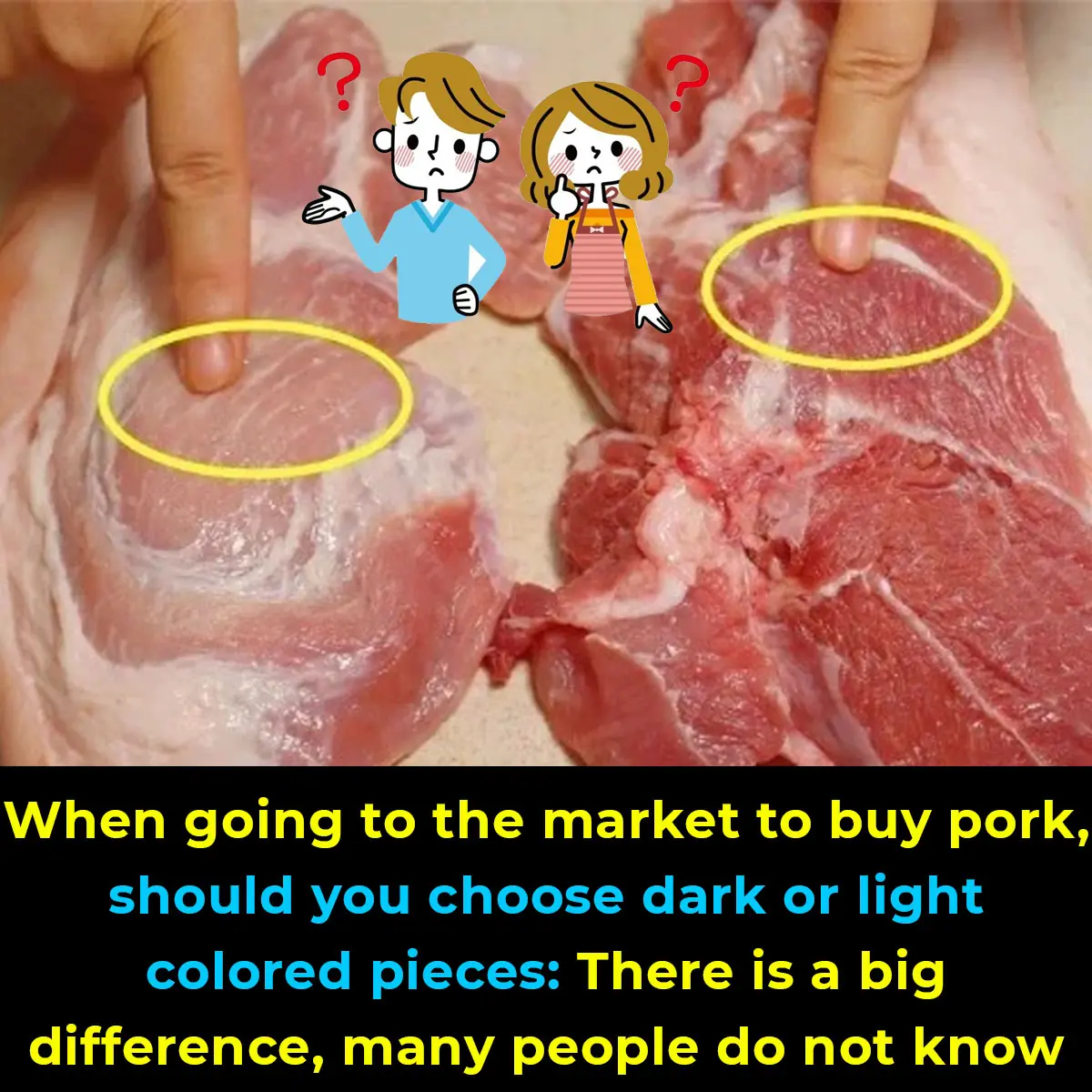

Tips for Selecting Fresh Pork at the Market

The Deficiency of These Vitamins Contributes to Panic Attacks

Researchers Find Higher Intelligence Is Correlated With Left-Wing Beliefs and Seems to Be Genetic

Urgent Health Warning Issued After Pigs With ‘Neon Blue’ Flesh Are Discovered in One Specific Part of the Us

25-Year-Old Groom Dies from Acute Liver Failure After Eating Chicken – Doctors Warn of One Critical Danger!

Doctors caution people with pre-existing liver conditions, weakened immune systems, or chronic illnesses to exercise extra care when handling poultry and other high-risk.

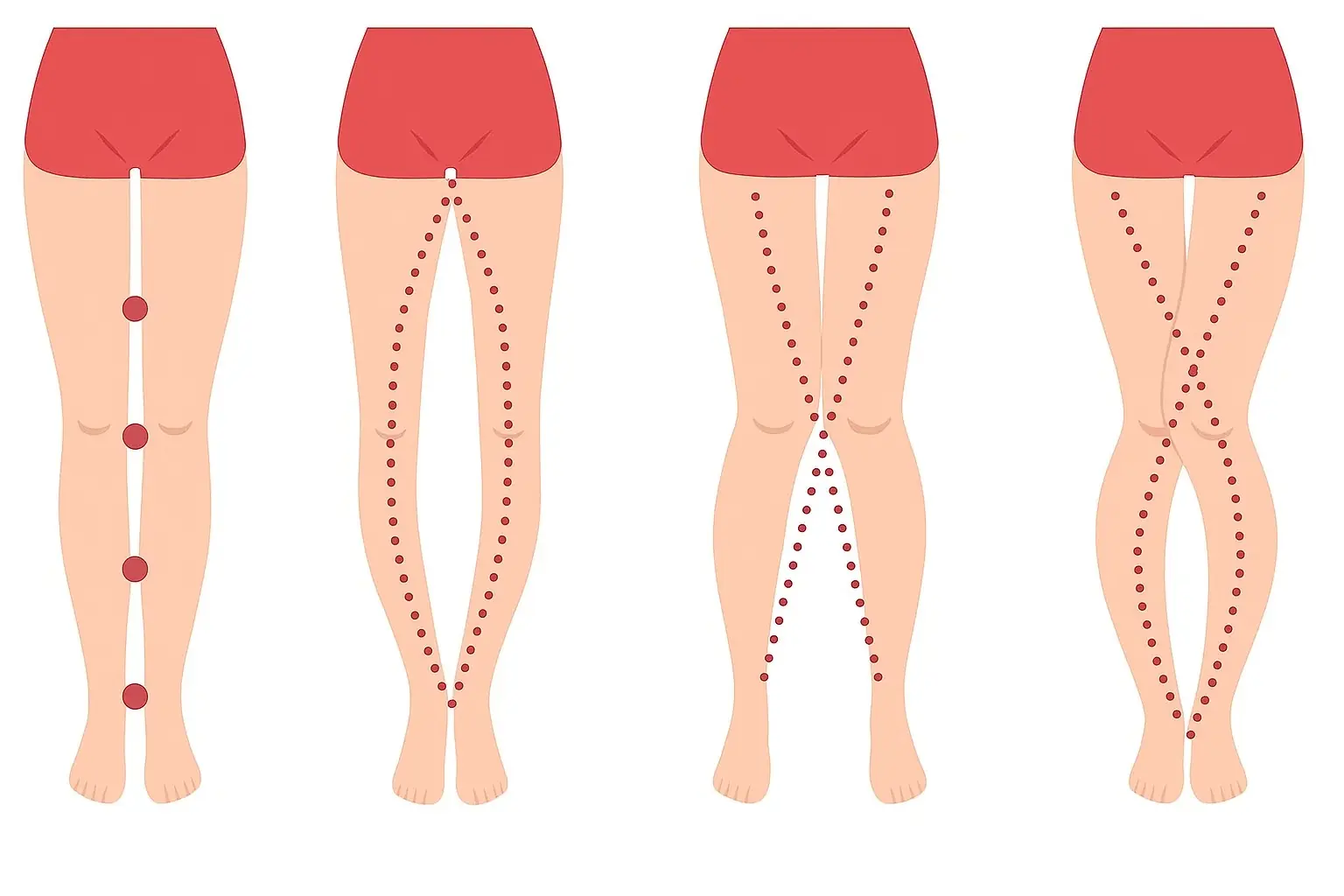

What Your Legs Can’t Say, Your Vagina Can — The Truth About the Female Body Most People Don’t Know

9 Areas Where Itching Could Signal Malignant Tumors — #7 Happens Most Often

The World’s Deadliest Food Kills 200 People Every Year — Yet 500 Million Still Eat It

Despite its deadly reputation, millions of people continue to eat this every day without issue.

Everything You Need to Know About Nighttime Urination And When To Start Worrying